Utterly pleased and terribly humbled to share with you Slow Motion Sober’s newest community feature - stories by YOU.

Today’s inaugural guest post (!) is by my dear friend and legit powerhouse, Amanda M. I met Amanda through my beloved Tempest community and was immediately struck by her humor, grace, candor, and a depth of compassion and wisdom that made me feel immediately comfortable and safe, despite only ever knowing each other virtually. She is a mother, an artist, a loyal friend, she’s quick to laugh with you (or cry), and she always, always, literally always knows exactly what to say to make you feel better.

It’s my honor to share her story with you today.

Last week I reached a significant milestone: 365 sober days.

I don’t identify as an alcoholic, although I’m sure that there were people who used that word to describe me. I only remember twice in my life that people dared to use that word to my face, both times met with a steely glare and an arched brow. I have always refused to accept what I think of as the new scarlet letter. The “A Word” is one that has been the gateway to freedom for so many problem drinkers, but to me it was just another trap, a shame-filled label for life, and even at the height of denial I had enough self-awareness to know that it was shame that made and kept me sick. I couldn’t give myself over to a higher power because the nexus of my illness was the sense of never having any power to begin with. Traditional 12-step recovery models hinge on drinkers admitting addiction and accepting that they were powerless and sick, given a death sentence by a disease with no cure. By contrast, I am a woman with more lifeforce than deathforce and for most of my adult life substance abuse was the grease in my wheels, keeping me just numb enough to push forward, paired with my relentless ambition to escape the small town Northern Ontario, struggling, dysfunctional, abusive trap that I was born into. I made it as far as London, England, about as far away as I could get from my family of origin without learning a new language. There’s an old saying “wherever you go there you are” and unfortunately I learned that no amount of success, money, privilege and society connections that came later in my life could save me from the ghosts of my childhood who whispered urgently in my subconscious that I would never really truly be safe.

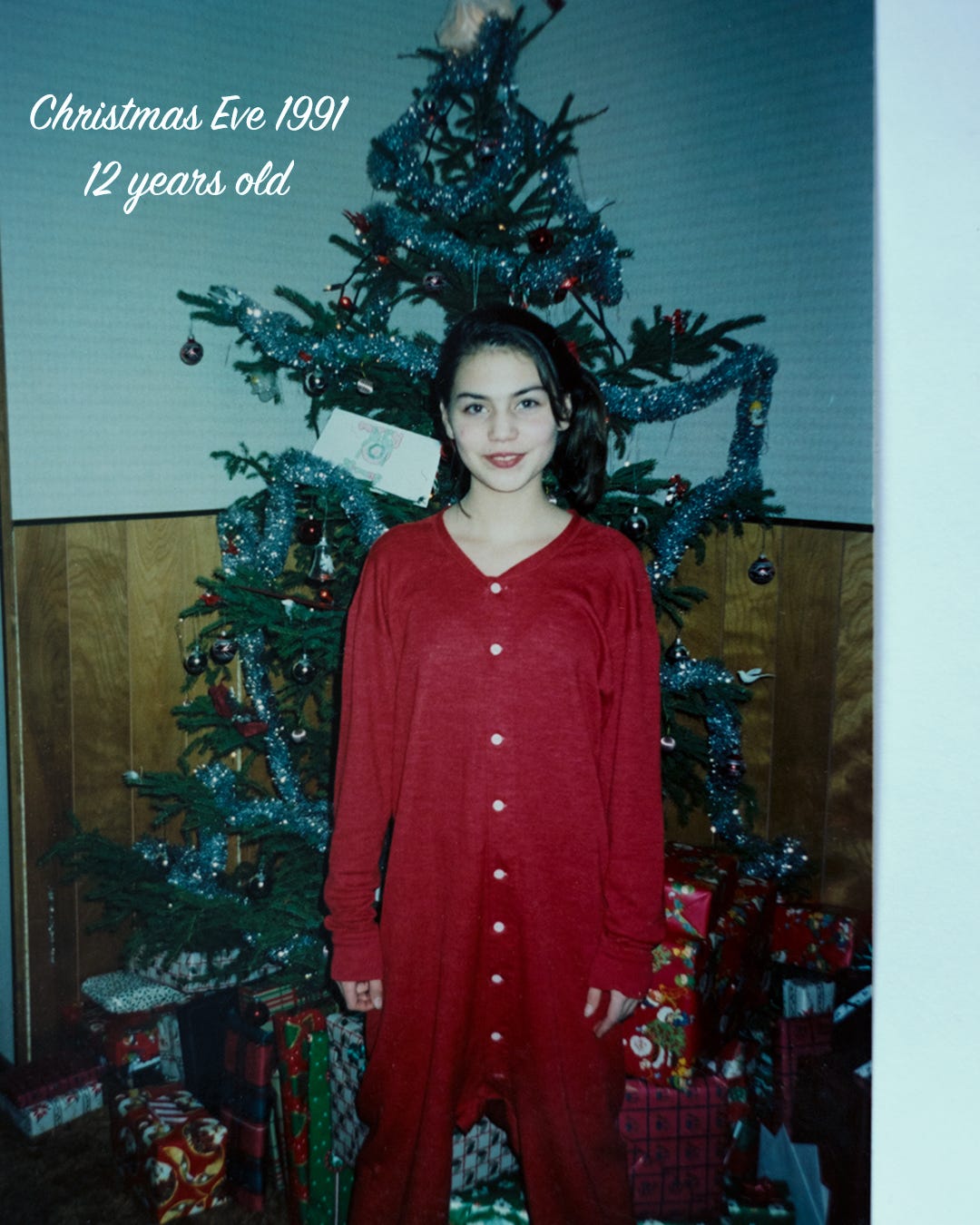

The first time I recall getting drunk was Christmas Eve 1991. I was twelve years old and allowed one Baileys and hot chocolate around the dinner table while my family played Pictionary and Balderdash. A member of my extended family kept slipping me more until I fell out of my chair, bashing my face on the radiator in front of the entire family. He thought it was funny. He was also the one who four years earlier had stolen what little innocence was left in my childhood bedroom. At several years my senior, he should have known better. He did actually, he just didn’t care. So began a pattern in my life familiar to so many women, of being targeted in safe places and led into danger only to wake up in the cold light of day ashamed and in trouble. I thought it was all my fault: I should’ve said no…I did something bad, therefore I am bad. The insidiousness of childhood abuse is that one’s abuser is usually canny enough to convince the child that they are complicit in the abuse, it also twists the child’s identity through a perversion of the mechanical advantage in sexual dynamics far beyond their years. It’s no coincidence that child sexual abuse victims are 5-times more likely to be sexually assaulted later in life. It completely rewires the part of your brain responsible for sensing and responding to danger. In my case sexual abuse coupled with emotional and physical abuse led to Obsessive Compulsive Disorder and risk taking behavior. When you vibrate on the frequency my mind does everything exists in extremes. When nowhere feels safe you live your life on the edge.

I developed anorexia and bulimia at 11, a response to the onset of puberty. Maturing physically left me vulnerable to the advances and catcalls of strange men, and worse, the prying eyes of those in closer proximity to my changing body. At 14, fully developed and naive to the fact I wasn’t really wise beyond my years, I discovered parties and the sex with older boys (men, really, who also should have known better). I also found the drugs and alcohol that go with them and didn’t look back, ever until I had children of my own. Choosing what went into my body and who could touch it gave me a (false) sense of control along with the bonus of a temporary but exhilarating escape from who I was and all the pain my tiny body was holding onto. For all of my family’s flaws one thing they are not short of is grit and ambition and I have it in spades. So, when older girls carved the word slut into the paint on my locker at school I held my head high. It stayed there all year. The school didn’t repaint it and I pretended I didn’t care while every whisper as I walked down the halls cut me like invisible shards of fiberglass, the scars hardening into a crest that I wore like a badge of honor under my clothes. My brother tells me the people in my hometown still call me that but it doesn’t bother me anymore—they can call me whatever they want. I’ve spent my adult life proving to myself that I am so much more than a woman who happens to enjoy sex. I was wild, that’s for sure, but as a mother of three girls I see something else now. I see a child who was broken and who was conditioned to play both the part of the victim and the criminal in a never-ending Karpman Drama Triangle.

I refuse to call myself an alcoholic for the same reason I refuse to call my teenage self a slut. It’s reductive, for a start, because there is a complex web of mechanisms that drew me into those scenarios, and both of them start and end with me having no jurisdiction over my own destiny. I’m not denying that I had a problem with drinking. It was always Russian Roulette whether I’d be the life of the party or whether things would take a dark or dangerous turn. What I am saying is that branding myself an alcoholic was not the key to my freedom, even though I accept that that has been the path of redemption for so many people before me. I’ve spent my whole life trying to step out of my shame cage, take my power back, to have agency, to be in control of my life and body. After several years of being sober-curious, I decided just over a year ago that my freedom looked like a sober life. I had found the Hip Sobriety blog online and was drawn in by Holly Glenn Whitaker’s post where she explains why she isn’t an alcoholic and why identifying as an alcoholic is not necessary to get well. I joined her online start-up Tempest Sobriety School which was the first beautiful, liberating step on the path back to myself. Who I found waiting for me there was a small, beautiful, smart, funny child with a broken heart. I also found a band of friends whose hearts looked like mine and my compassion for their stories and the rage and empathy I felt on their behalf brought the ghosts of my past into sharp relief—only I see them differently now. The people I’ve met in Tempest held a mirror up to my own experiences and have given me the grace to love myself again, as I love them in all their imperfect perfection.

I’m estranged from most of my family of origin now, mostly in honor of the emotional health of the family I made for myself: my partner, my children and the band of incredible people who I’ve chosen as friends. These people need me, as I need them. As heartbreaking as it is, some of those people that I came from pollute my heart and mind worse than any of the substances I used to escape what they did to me. I simply “cannot” with them anymore and it took getting sober to realize that I needed to lift the drawbridge leading me to them one last time, lock it and throw the key into the swampy water of the moat that divides us. (Thank you Glennon Doyle for that analogy, if you’ve not read Untamed it’s a revelation) A psychiatrist once told me I was an anomaly, that “people with histories like yours don’t usually make it, they succumb to addiction or suicide. I don’t know who you had in your life or what you had inside you that got you so far, but what strikes me is how much you have going for you.”

Honestly, I had no fucking clue.

This year on Mother’s Day, a day traditionally spent downing expensive drinks to escape my loneliness and heartbreak over my familial estrangement, I sat instead soaking in an epsom salt bath, with the peppermint and lavender water pooling around my body, and I was just so ecstatically grateful. I am grateful for my body which has carried me so unconditionally, grateful for the family I have chosen, my daughters, grateful to be alive. I sat there in the warm water and went into a meditation and a vivid memory came to me. I am six years old in the backseat of a car at the dump. I am holding an old triangular costume jewelry brooch that the pin had broken off of and it is a priceless treasure to me. I rub the plastic red gemstone in the centre and I imagine that it grants wishes. I wish to be grown up, and strong and free and not sad all the time. I wish to be safe. Suddenly I’m back in the bath and the triangle reminds me of the Karpman Drama Triangle that I broke as I pulled away from my family. I love that little girl, I love her with all my heart and I want to rescue her from that place and take her far, far away with me. Then a voice inside of me says “It was always you, you were here all along. Time is a loop and you loving that little girl now is what got you through, you are the one who set you free.”

Fast forward to today and I want to point out that I wrote 365 sober days, not 365 days sober. This is because they weren’t consecutive. In a 12-step program, I’d have had to start over counting days. I slipped a few times, mostly when I felt powerless or angry. Anger is still a beast I am trying to love into submission, and at the same time—though the violence inflicted upon me in the past leads me to fear my own anger—I recognize it now as a gift. Anger tells me when something has touched a place in me that needs protecting. Anger is a sign to pull up the bridge. After each one of those short lapses with alcohol, I asked myself to see the gift that was being offered me, and each time I learned something about the limits of my distress tolerance, when I needed to set a boundary, or simply when I needed to fall to my knees and hug that child inside me and then I’d get back up, set the counter back a day and keep counting. One of the central themes in Tempest is “I make the rules I live by.” Another is “I can begin anew every day.” I’m not an alcoholic, I am a person who chooses not to drink. Every single one of those sober days count, every day is a gift and a lesson. I fought so hard for those days, they are mine and there is nothing and no one that will ever take them away from me or measure what they mean. I am my own mother now.

Amanda is a Canadian photographer and creative director living in London, UK. She has three daughters and lives with her children, fiancé and their rescue cat Peter Parker.

Slow Motion Sober is a newsletter and community for creative types who are sober or curious about sobriety, and all the life-y intersections along the way. It's written by me, Dani Cirignano, a writer and sobriety advocate in San Francisco, CA.

SMS is reader-funded. The small percentage of readers who pay make the entire publication possible.

You can also support me for free by pressing the little heart button on these posts, sharing this newsletter with others and letting me know how this newsletter helps you. Thank you.

Amanda, this is so moving. Beautifully written and inspiring too. Thank you so much for sharing your incredible story. You are indeed a woman with a powerhouse life-force.

Amanda, thank you so much for sharing your story. It resonates so deeply. Wow your strength is dynamic. Inspired.